Desertion, theft and a stay in hospital: Alfred Lennon’s eventful war

Newly-discovered ships' records reveal how John Lennon’s father jumped ship in New York and was imprisoned in Algeria for stealing cargo, before being hospitalised in Italy with venereal disease.

In the winter of 1943, John Lennon’s father Alfred was working as a steward on the Moreton Bay – a passenger cruiser now converted for carrying troops during the war. Crossing the Atlantic back to Liverpool after a stop in New York, the ship encountered a terrifying three-day storm.

A log entry, dated 22 to 24 January, tersely notes: “Vessel in convoy in intense cyclonic disturbance, with mountainous seas.” Manoeuvring to ride out these conditions, the Moreton Bay sustained “upper structural damage”, with its lifeboats and rafts affected. The chaos may have hastened the end for one of Alf’s crewmates. At 1:30am on the third day, Albert Grant, a 28-year-old fireman with suspected meningitis, died; he was buried at sea that afternoon. His remaining personal effects included a three-piece suit, six chocolate bars and two tins of meat extract.

Grant’s fate was by no means unusual for merchant seamen, whose death rate during the second world war was higher than for those serving in the armed forces. Misfortunes experienced by others on the Moreton Bay included suffering a skin infection, having their appendix removed or losing a fingertip. But these crew members, and the rest of their colleagues on board, were all lucky: they returned home at a time when many were not. The threat from prowling German U-boats was then at its peak, with alarming numbers of merchant vessels being sunk.

The North Atlantic was particularly perilous, so Alf – now aged 30 – was probably grateful to reunite with his wife, Julia, in February. But when he got back, he found his domestic life was also undergoing upheavals. The four-year marriage had always been idiosyncratic, punctuated by Alf’s long absences at sea. Now real problems were emerging. After an argument about Julia’s new habit of visiting the pub “every evening”, Alf says she poured hot tea on him; he responded by slapping her1.

Clearly, there was a lot going on in Alf’s life. But as it turned out, all this was just the prelude to far greater disruption. He was about to embark on extraordinary series of global escapades – beginning in July 1943 and lasting well over a year, with each mishap compounding the last. Alf’s own telling of these events is barely believable. But I’ve found archive documents that reveal an even more remarkable story. Meticulously-kept logs, crew agreements and other records detail how John Lennon’s father deserted his ship in New York, was imprisoned in Algeria for stealing cargo and then – in an episode Alf didn’t mention – hospitalised in Italy with venereal disease, before returning to the UK as a ‘distressed British seaman’.

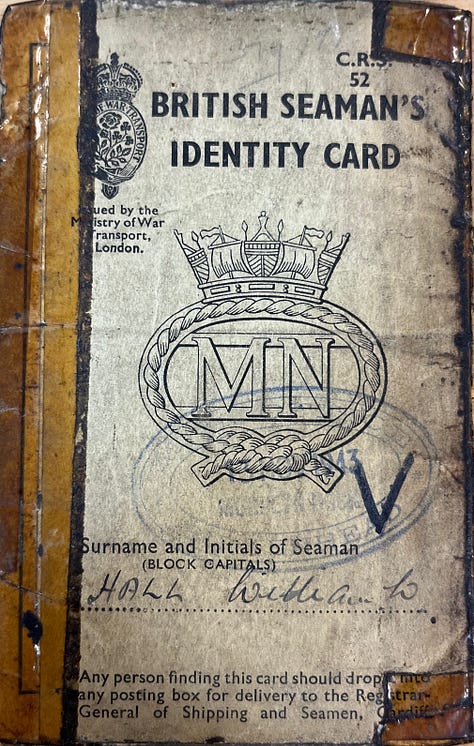

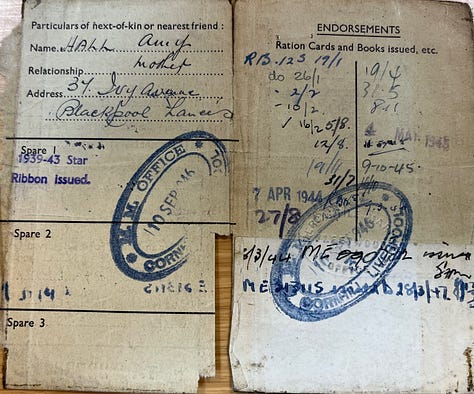

Along the way, Alf befriended Billy Hall, thereby paving the way for a later, much-discussed incident in Blackpool – where a five-year-old John Lennon was supposedly asked to choose between emigrating to the antipodes with his father, or staying in Liverpool with his mother. Below, I take a closer look at what happened – including a definite answer on whether we can believe Alf or Bill about how the latter got to New Zealand.

The details of ship movements, desertions and events on board are all confirmed in documents held in the UK National Archives. Some additional context and quotes, from Alf’s perspective, come from his quasi-autobiography Daddy, Come Home (1990)2.

Deserting ship in New York

It may have at least partially mitigated the hardships of his employment when, while serving on the Moreton Bay in May 1942, Alf Lennon had been promoted from assistant steward to saloon steward. It involved a pay rise of a pound a month: about 10%3. Alf continued in this role on the ship’s next trip, which – following the storm – returned to the UK in February 1943. Alongside its risks, that voyage epitomised the work’s adventurous glamour – having called at ports including Durban, Buenos Aires and Trinidad before reaching New York.

By July, the Allies had seen off the Atlantic U-boat menace. Alf now sailed this route in the other direction – this time as a passenger, travelling to the US in the apparent hope of a much bigger role. He claims that in a pub, a union official had told him that seamen with ratings such as his were sent to New York for jobs as chief stewards on ‘liberty ships’. (At the time, these mass-produced vessels were rapidly being built to replace the huge numbers lost.) While the new ships did urgently require staffing, chief steward was a senior post overseeing all catering crew: well above even Alf’s new level. So his supposed plan sounds rather optimistic – but it may nonetheless have been with a sense of new possibilities that he made the journey.

As it happened, Alf had to wait for weeks in New York to be assigned to a ship – long enough to find a temporary job at a department store, Macy’s. A keen singer, he also quickly found a way to express his creative side, spending his weekends entertaining other seamen in bars. He fondly recalled one particular occasion, when he performed his “Adolf Hitler act”, followed by some Broadway musical numbers and an “impromptu dance” around the room – “leaping across tables into the hairy arms of the sailors… The finale was greeted with stupendous applause and shouts of ‘Broadway for the boy’.”

Alf said this tour de force – which allegedly led to him being held aloft through the New York streets, followed by a crowd of forty to fifty revellers – “was one of the greatest thrills of his life”. But joining the crew of the Samothrace in Baltimore that September, cold reality struck. Given his recent promotion and hopes for more, it must have been a bitter blow to be employed at his former level of assistant steward. There was then more bad luck on board when Alf broke his right collar bone wrestling with a crewmate. The injury kept him off duty for more than three weeks. With his frustrations mounting, a spirit of restlessness perhaps proved overwhelming, and while at port in New York on 13 January 1944, Alf Lennon deserted the Samothrace, “taking all his gear with him”4.

Prison, then hospital

Perhaps, as Alf claimed, the ship’s captain had told him this would be the only way to register a complaint about his rating. Perhaps Alf, who as a boy had dreamed of a career on stage, even had visions of extending his run as an entertainer. According to Daddy, Come Home, Alf reported to the British consul the day after jumping ship. (His naval service file shows he was listed as “man wanted”.) In Alf’s telling, his innocent request for help led to him being detained on Ellis Island for two weeks by the immigration authorities. Whatever happened, we know for sure that on 9 February 1944, Alf joined another liberty ship, the Sammex, headed for North Africa.

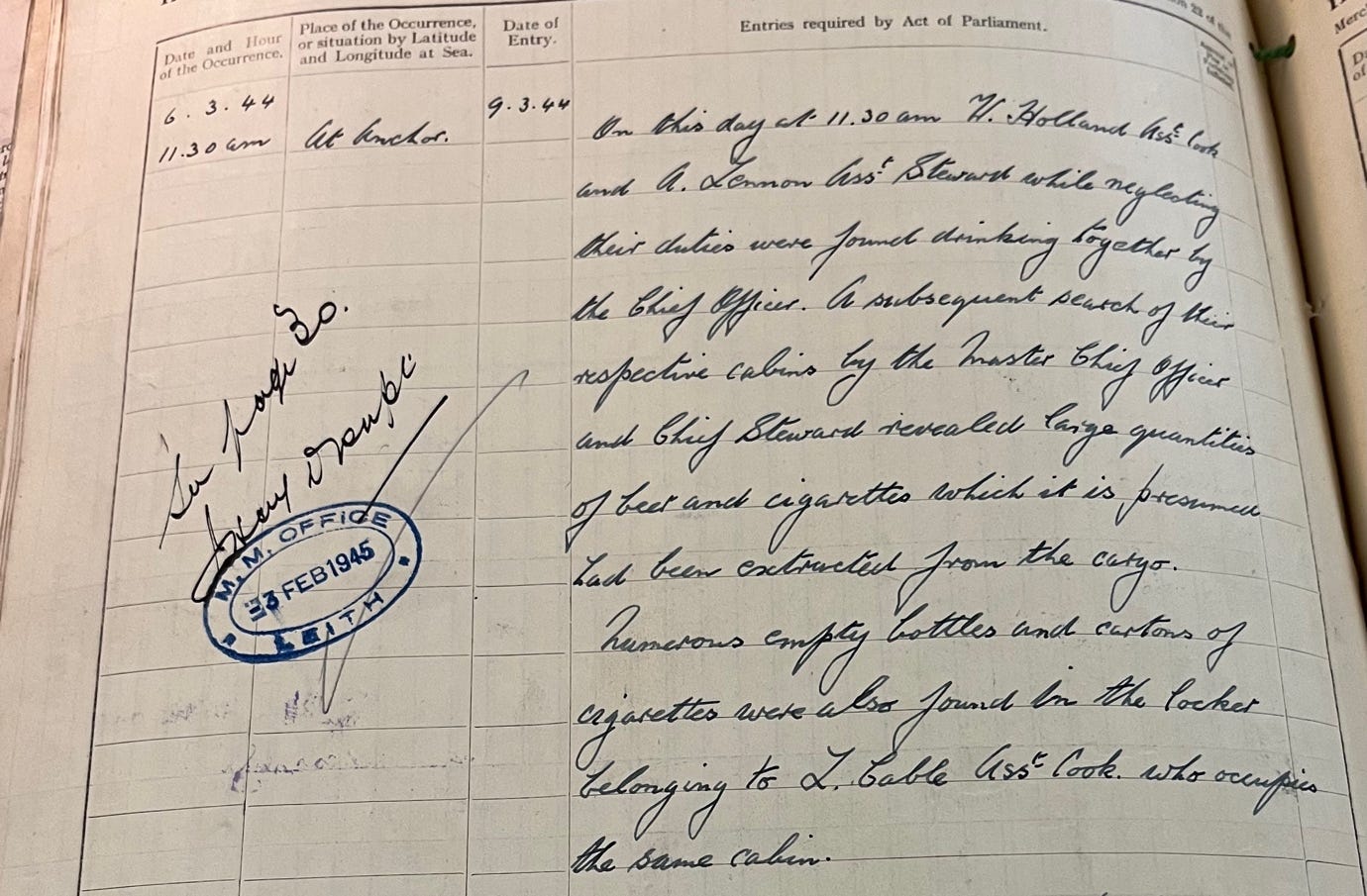

Alf remained at the level of assistant steward – though that turned out to be the least of his troubles. The Sammex’s log records that about a month later, he and another crew member were found “drinking together” at 11:30am while “neglecting their duties”. A search of their cabins “revealed large quantities of beer and cigarettes which it is presumed had been extracted from the cargo”. According to the entry, Alf claimed that “similar pilfered goods” would be found in the cabins of all the vessel’s officers and of other crew members – but a search found this accusation was “unfounded”.

This contrasts markedly with Alf’s own account, in which he resisted being drawn into an on-board conspiracy to broach the ship’s cargo – but was then unfortunately caught drinking stolen beer, just after his friend had left the room. His story must have failed to convince the naval court at the next port – Bône in Algeria5, an important hub for the North Africa campaign. Here Alf Lennon, together with two others, was sentenced to imprisonment. Months after his star turn in the bars of New York, he now found himself in Bône’s military prison in conditions he would later say were “so disgusting as to be indescribable”. Despite his sentence being for two months, Alf’s service file says that he only spent a month there, for “embezzling beer and cigs”. This, though, was by no means the end of his travails.

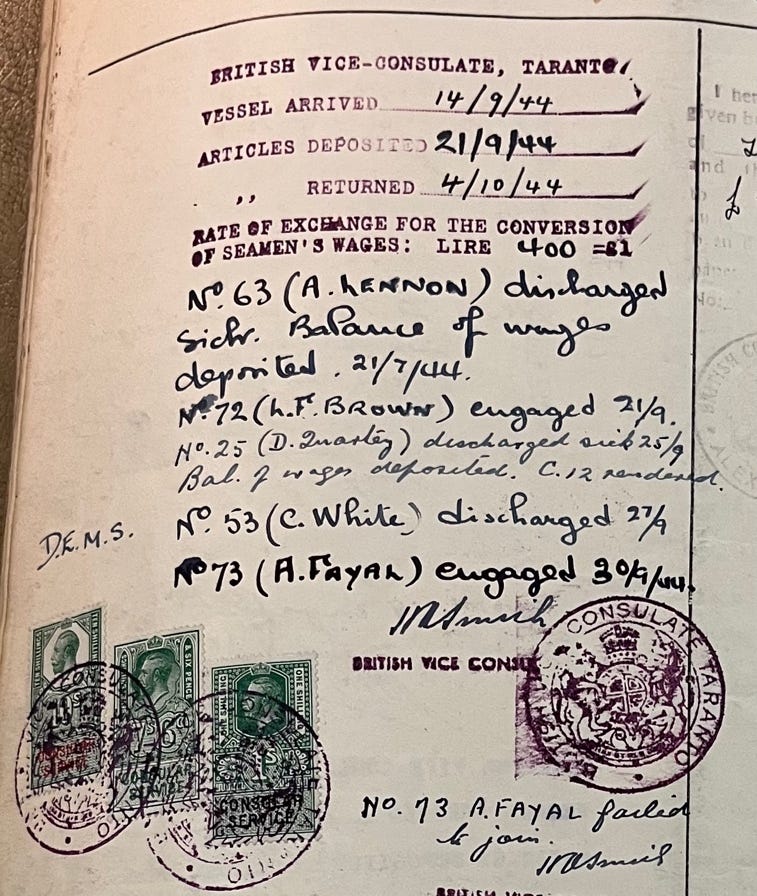

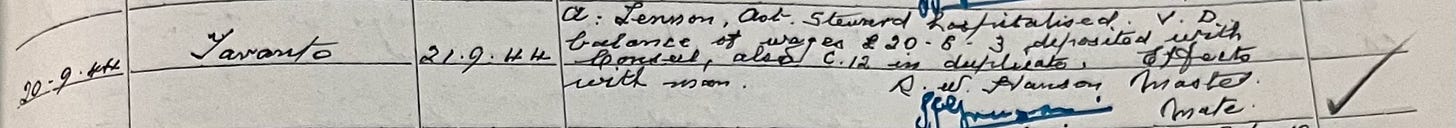

Following his release, Alf was sent to Algiers, where he boarded the Chiswick on 27 May. After traversing the Mediterranean between Italy, North Africa and Greece, this ship would return to Birkenhead, opposite Liverpool, early the next year. But if Alf was hoping for an uneventful voyage home, this was not to be. A few days later, the vessel experienced “very severe vibrations” at sea after “seemingly [being] hit” during an enemy air attack6. Upon inspection, no serious damage was found – but the incident nonetheless highlighted the danger of the work. While the Chiswick survived this scrape, later that year Alf suffered further misfortune. On 20 September he was discharged from the ship to a hospital in Taranto, Italy with “V.D.” – venereal disease, or what would now be called an STI.

The condition was not unusual among sailors (the Chiswick’s log records three other crew members hospitalised with VD on the same trip). But in Alf’s case, this information calls into question statements he made about his marriage. With the infection emerging 14 months after he was last in Liverpool, it appears to contradict the claim of Alf’s “unerring faithfulness”, which is made in Daddy, Come Home to contrast with the actions of Julia (by the time Alf returned, she was pregnant by another man)7. Ultimately, it’s impossible to know in what circumstances Alf acquired VD. But if he hadn’t, any conversation about whether he or his son might move to New Zealand would, perhaps, never have happened.

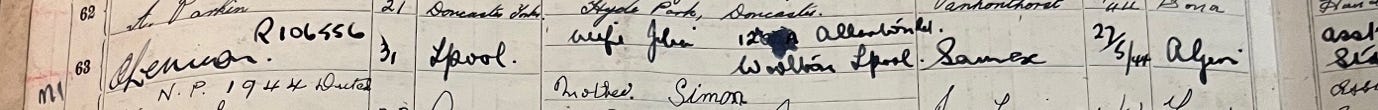

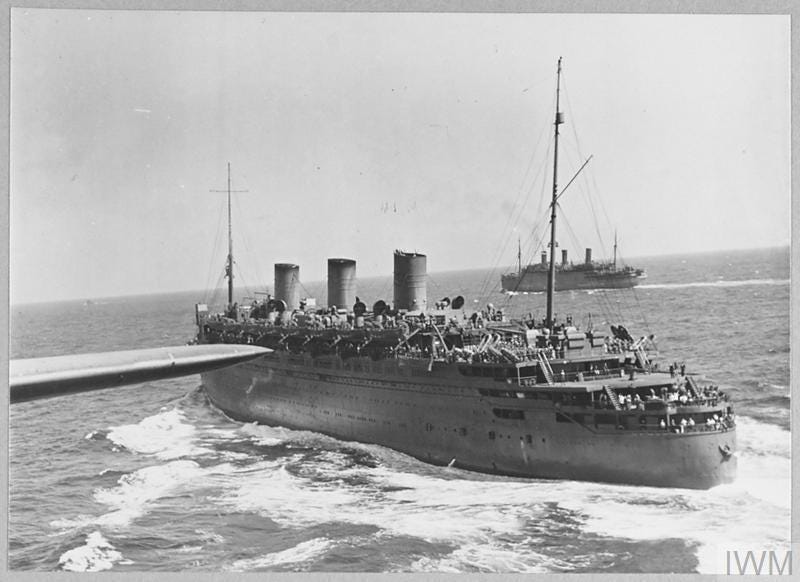

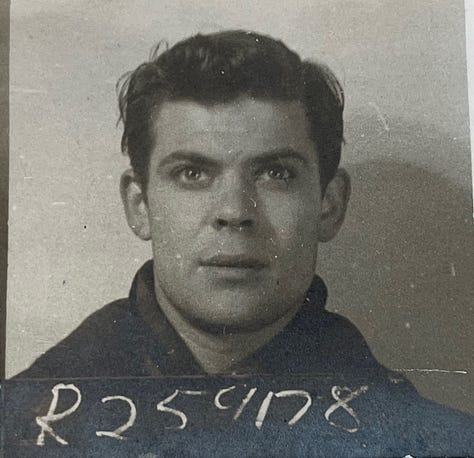

Within a few weeks, Alf was out of hospital and in Naples. It was here, on the 11 October, that he was one of more than 50 “distressed British seamen” collected by the Monarch of Bermuda for repatriation to the UK. Working as a bedroom steward on the same vessel was 21-year-old William Hall of 37 Ivy Avenue, Blackpool. Despite Alf’s claims that they met in Algeria, it was presumably on this voyage, then – in the 12 days between Alf boarding and the ship getting back to Liverpool – that Alf and Billy became friends.

High jinks in Australia and New Zealand

Returning home after the trip – the Monarch of Bermuda docked in October 1944 – any relief Alf might have felt was quickly tempered with the surprise of Julia’s pregnancy (the father was a Welsh soldier named Taffy Williams8). This shock news came just as hope was resurgent in wartime Britain. Following the success of D-Day, the Allies were advancing in Europe on two fronts, and thoughts were turning to what would happen after a victory that seemed increasingly likely. It was amid growing national optimism, as well as personal uncertainty, then, that Alf would reunite with Bill Hall for their next voyage – on the Dominion Monarch, flagship of the Shaw Savill Line. The trip included locations with a special appeal to each of them: for the former, New York and for the latter, New Zealand.

In November, Billy boarded the ship in Liverpool as assistant steward, travelling to New York and back before Alf joined the crew on 28 December (in the same role as Bill). It must have been after this date that Hall’s photograph of “five good friends” – himself, Alf, Billy’s brother John and two others – was taken9. The records confirm that all five were on board – and in further evidence of this gang’s closeness, they were often found together in the groups of crew disciplined for going absent without leave (Awol).

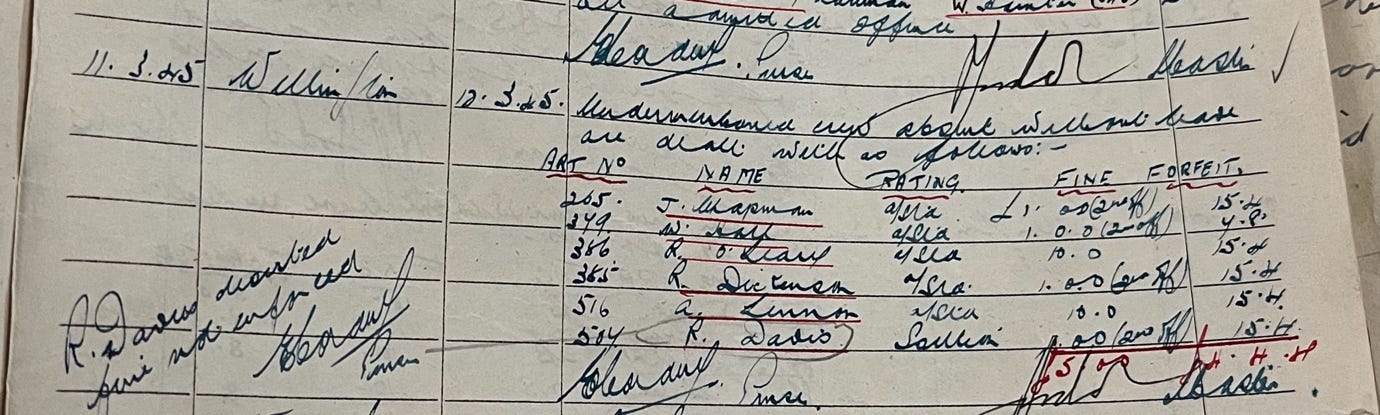

On 2 March 1945, for instance, while the Dominion Monarch was docked at Sydney, Bill, Alf and John Hardacre (another of the five friends) were all among a group of eight crew fined and forfeited wages for being Awol. The following week, in Wellington, Alf and Bill were penalised once more for the same reason. And at the end of that month, at Balboa in Panama, Alf – together with John Hall and Frank Leedale, the fifth friend – was again disciplined. These records chime with the recollections of Bill Hall, who said in reference to Alf: “He was a pisshead. We all were.”10

The evidence we have, then, suggests a compelling picture. The end of the war was increasingly in sight – and after many tough years at sea, discipline was flagging. Finding themselves in exotic locations among agreeable company, it seems that the temptation to indulge in high jinks was irresistible. For Alf in particular, the trip was probably a welcome relief after his various ordeals. Bill had already been to New Zealand twice, and loved it. It may well have been on this third visit that he began to seriously consider moving to the country – and possibly suggested that his friend do the same. After a brief stop in New York, the Dominion Monarch returned to Liverpool. Alf and Bill disembarked on 20 April 1945, less than three weeks before VE Day.

The Blackpool conversation

After the voyage, the five friends went on leave to Blackpool: photographs show members of the group – sometimes alongside Hall’s parents and others – relaxing, drinking and larking around (in one, taken “after a session” at a local pub, Bill leans jokingly over Alf wielding a hammer). After this, though, Alf and Bill appear to have gone their separate ways until the former returned with his son the following year. Alf worked three more trips on the Dominion Monarch, before joining the Queen Mary for a short engagement – employed as a night steward from to 13 April to 1 May 1946. Meanwhile, Bill served on the Île de France, followed by two voyages on another impressive ocean liner, the Queen Elizabeth. His strong record of service is reflected in the award of a campaign medal, the 1939-1943 Star. But after the war, Hall’s service file shows that his engagements abruptly ended. In October 1945, he “failed to report from leave”, and worked on no more ships until being released from the Merchant Navy almost a year later “on termination of war service”.

Meanwhile, the young John Lennon’s domestic situation was becoming increasingly fraught. His mother, Julia, had given birth the previous June, with the baby adopted. Soon afterwards, she found a new partner, Bobby Dykins. During these events, John’s aunt Mimi had spent plenty of time looking after him at her house. But in spring 1946, Julia and Dykins moved into a tiny one-bedroom flat, taking John with them. Soon afterwards, apparently with the support of Liverpool City Council, Mimi had removed John – citing concerns about him sharing a bed with his mother and Dykins – to go and live with her11.

Upon his return to Liverpool in May, Alf apparently felt the need to intervene in this situation. The next month, he visited Mimi’s house and departed the following day with John. Alf says he told Mimi he was taking his son “shopping or to see his Granny”. In fact, the two went to stay with Billy Hall in Blackpool.

This was where the conversations about John’s future took place. While we may never know for sure what was said, the evidence above suggests that Bill Hall is a far more reliable source than Alf Lennon – whose account differs widely from what the documents reveal. This becomes even clearer when we compare the archive records to Alf and Bill’s differing stories of how Hall left the UK.

According to the testimonies of Hall and his family, he jumped ship in 1947 from the Arawa, with his parents following years later. Alf, however, told a very different story. In his version, the Hall parents emigrated first – then Bill deserted the Dominion Monarch some time after summer 1948, while Alf was also on board. Alf claimed he planned to follow suit – only changing his mind at the last minute in Wellington in 1949.

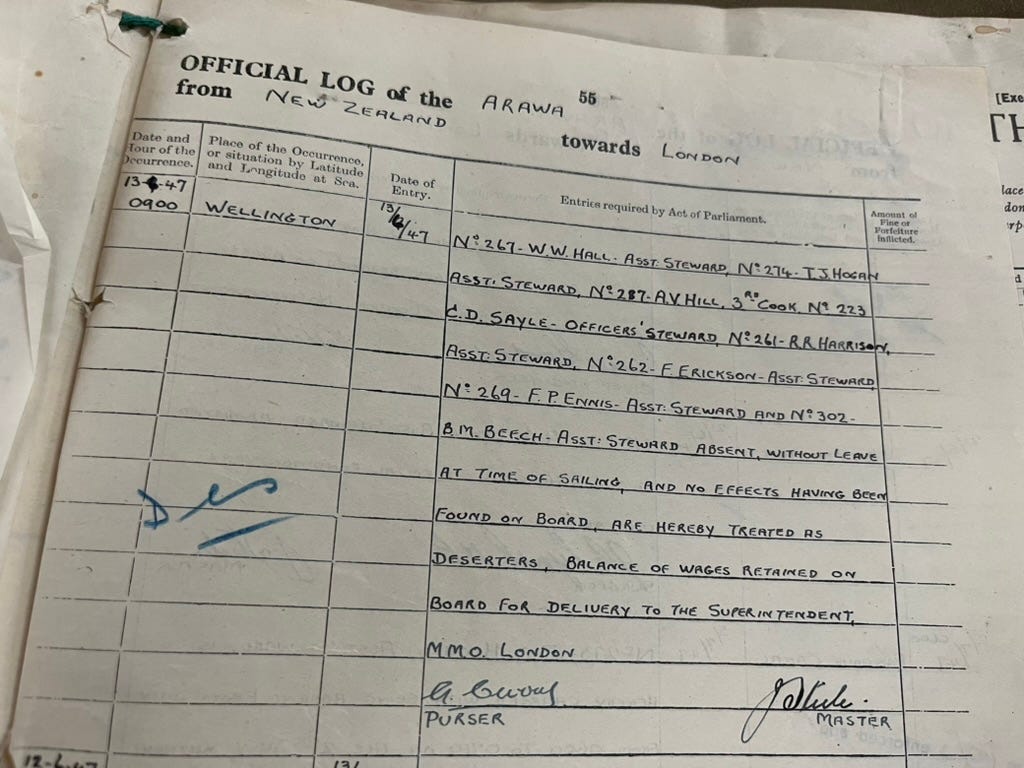

Here, the archives are unambiguous on who we can trust. Bill’s service record shows that he rejoined the merchant navy on 7 March 1947. He boarded the Arawa as an assistant steward the next week, then went Awol on 11 June while the ship was docked in Wellington. When Hall failed to materialise for the return voyage two days later, the ship’s log confirms that he was written off as a deserter. Highlighting the popularity of such a move at this time, the records show that ten other men jumped ship during the Arawa’s three and a half week stay in the New Zealand capital.

Clarifying the story

So Bill’s recollections largely match the documents – but what about Alf’s? Ships’ records do confirm his account that following the events in Blackpool, he departed for long spells on the Almanzora and then the Andes. These were followed by three successive voyages on the Dominion Monarch in 1948 and 1949 – all of which called at New Zealand12. Similarly, Alf recalled trips on this ship in these years. Indeed it was during one such voyage – sitting in a pub in Auckland on a “beautiful spring-like Sunday in October 1949” – that he says he was intending to jump ship the next day – until a crewmate asked him: “You’ve a son in Liverpool, don’t you Freddie? Won’t you miss him?”.

The log for Alf’s last trip leaves open the possibility that he may indeed have been on the cusp of moving to New Zealand. The Dominion Monarch, with Alf Lennon on board, called at Wellington on 14 October 1949, staying for almost a month. On the day of its departure – 12 November – Alf was one of ten crew members fined for having gone Awol. The same day, the log noted that nine other seamen had deserted. But if Alf had considered joining the latter group, it was his last chance. The next month he returned to London, and would never work on a ship again.

The records, then, are largely compatible with Alf’s description of his last-minute change of heart. But deciding how much trust to place in his tales is a complex matter. For someone evidently comfortable with stretching the truth, many of the details he provides are surprisingly accurate. Then again, some of his most significant claims are way off the mark. These include his story that Billy Hall deserted the Dominion Monarch, which must simply be an invention. Bill didn’t work on that ship after 1945 – and records clearly show he fled the Arawa in 1947, before the Dominion Monarch had even resumed service after the war.

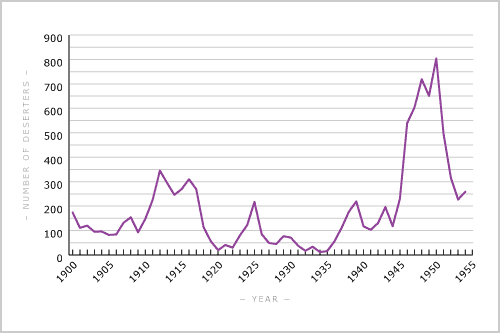

Ultimately, though, the documentation of Alf and Bill’s time at sea doesn’t just help clarify the facts. It also supports a deeper understanding of the situation that came to a head in Blackpool. Clearly, the idea of moving to New Zealand wasn’t just a passing thought. As the chart below indicates, huge numbers of merchant seamen deserted their ships to live in the country after the war. Bill Hall was one of them, and Alf Lennon may have seriously considered joining him there. He had visited the country numerous times, and his marriage had broken down. The problem with Alf’s account is not the impracticality of him emigrating, but of taking his son with him.

Post-war deserters at New Zealand ports

I’ve come to realise that this subject is also far more relevant than it first seemed to my research about the Beatles in Greece. Alf’s story gives us a valuable new perspective on the personality of John Lennon, the chief proponent of the group’s plans to buy a Greek island. Curiosity about his father’s wartime escapades may help explain why John developed a growing interest in sailing and the sea, for instance. It could also have contributed to the Beatle becoming (in Paul McCartney’s words) “a world war two buff” with a “complete set” of Winston Churchill’s works13.

What’s more, there are some fascinating parallels between Alf’s and John’s lives. Almost two decades after Alf wowed the New York crowds with his Hitler impression, his son’s band came of age in another foreign port, Hamburg – once again, entertaining off-duty sailors with off-the-wall antics. Alf, who visited New York many times, suggested that in different circumstances he would have liked to live permanently in the city – something John did of course do (as well as following in Alf’s footsteps to Wellington and Auckland, on tour with the Beatles in 1964).

Getting a better grasp of Alf’s character may also help us appreciate why John was drawn to certain people. The evidence reveals his father as roguish, talented, and unpredictable; an engaging companion, though an ultimately unreliable one; an entertaining storyteller who blended elements of the truth with wild distortions. And controversy seemed to follow him wherever he went. Does that remind you of anyone else? Substitute the Scouse accent for a Greek one, and it seems to me those words could just as easily be describing Magic Alex.

Read more:

Daddy, Come Home says this was “the one and only occasion he ever struck her”.

Daddy, Come Home is authored by Pauline Lennon (Alf’s second wife) but the book says it is “largely based on the text of Freddie Lennon’s unpublished autobiography”. For convenience, I refer to it as Alf’s account.

Moreton Bay ship’s log, The National Archives

Samothrace ship’s log, The National Archives

Bône is now now called Annaba

Chiswick ship’s log, The National Archives

The book also says that Alf “remained faithful to Julia from the beginning to the end of their relationship”. The question of Alf’s fidelity on his travels is also discussed in Mark Lewisohn’s major Beatles biography, Tune In (2013 – extended special edition). Lewisohn says that if Alf’s claim of being “sexually loyal” was true, he would have been “holding back where mates probably didn’t”. On the basis of Julia’s perceived coolness towards Alf, Lewisohn expresses the view that “quite why he was saving himself seems hard to fathom”.

According to Alf, Julia said Williams had raped her, but this is not stated in the accounts of the events by Julia Baird (John’s Lennon’s half-sister) in John Lennon, My Brother (1988) and Imagine This (2007).

Bill Hall’s note says the photograph was in 1944. If this is accurate, it must have been taken soon after Alf boarded the ship, in December. A southern hemisphere location is arguably more likely - in which case, the photograph must have been taken in 1945.

Interview in the Sunday Star-Times, 8 March 2009

Julia Baird relates these events in John Lennon, My Brother (1988), and Imagine This (2007)

Alf also worked on the Dominion Monarch between 12 and 15 November 1948 – travelling from Newcastle to London ahead of the ship’s first foreign trip following its refit.

McCartney: A Life in Lyrics podcast (Pushkin Industries). Season 2, Episode 7: A Day in the Life

John was certainly susceptible to, dare I say, daddy figures who promised big things that weren't always attainable in reality. Allen Klein also comes to mind.