The 'Blackpool incident': what we've been overlooking

Billy Hall, a good friend of John Lennon’s father Alfred, emigrated to New Zealand after the second world war. Did Alf intend to join him there?

Update - read my research on Alfred Lennon’s wartime experiences:

At lunchtime on 23 February, 1941, the Tongariro cargo ship pulled into Auckland harbour amid summer breezes. For Billy Hall, a seventeen-year-old steward’s boy on board, the trip was only his second time at sea. The first, the previous year, had been a brutal introduction to the perils of the ocean – getting shipwrecked off the coast of Scotland. Alongside such natural dangers, as a merchant seaman in the second world war, Billy faced the constant risk of enemy attacks. Against this backdrop of hardships, the allure of the antipodes made a huge impression on him – a striking change from his home town of Blackpool. Billy visited New Zealand three times during the war. While his ships were docked, he might spend all day with crewmates in the bars of Auckland, or attend a vibrant party in a Wellington suburb. “I thought it was Godzone,” he later recalled.

As strong as Billy’s growing love for the country was his hatred of Britain’s class system. He’d seen his father queue for the dole for almost a decade: he was fired from his job in a bleach mill after injuring his arm. So after the war ended, the decision to move to New Zealand was easy. Like hundreds of others at that time, he simply got off his ship in Wellington and never got back on. Billy found real success in his new home: first as a fashion entrepreneur, then as a pioneering game fisherman. By the time he died in 2013, aged 90, he could look back on a remarkable path through life. What made it even more remarkable was that for a brief few weeks, it overlapped with that of a Beatle.

During his travels, Billy befriended another merchant navy steward: Alfred Lennon, father of the future Beatle, John. And after the war, Billy was present for a significant event in John’s childhood: one that has often been seen as “foundational”1. In Blackpool in June 1946, the five-year-old John was supposedly asked to choose between moving to New Zealand with his father or staying in Liverpool with his mother.

Beatles biographers such as Hunter Davies and Philip Norman have recounted this story, based on accounts from Alfred. For many, the heartbreaking choice has seemed to crystallise the future Beatle’s childhood trauma. (Norman wrote: “If you want to tear a small child in two, there is no better way.”2) Personally, I’ve speculated that an association in John’s mind between that parting with his father and the idea of moving to an island nation may have influenced his later psychology and fascinations.

However, in Tune In, the first part of his planned three-volume Beatles biography, Mark Lewisohn reported an account from Billy Hall, who told him that there was “no truth … at all” in key elements of the conventional story.

The revelation was seen as one of the book’s major myth-busting moments. And much of the Blackpool myth did indeed need busting. But since I began to explore this story, I’ve found there’s still more to say about it. I hadn’t realised, for instance, that Billy Hall did actually move to New Zealand. After speaking to members of Hall’s family, and researching his friendship with Alf through archive records, I’ve been able to gain a much clearer picture of other aspects of the events, too. What I’ve discovered not only allows us to better understand what happened in Blackpool, but also helps separate fact from fiction regarding Alf Lennon’s extraordinary wartime experiences – including significant new information. But first, let’s take another look at the traditional tellings of the Blackpool story.

The Blackpool story

In June 1946, John’s father Alfred (better known as Freddie or Alf) – an infrequent presence throughout John’s early years due to his work as a merchant seaman – reappeared in his life. John, then aged five, had recently gone to live with his aunt, Mimi, after his mother Julia (now separated from Alf, though still married to him) had moved in with her new partner, Bobby Dykins. Apparently concerned about John’s situation, Alf visited Mimi and took his son to visit Blackpool - a traditional seaside resort. John and Alfred stayed in the town for a few weeks with Billy Hall and his parents.

With the war now over, Billy was planning to emigrate to New Zealand – and according to the Beatles’ authorised biographer Hunter Davies3, Alf decided to join him. As these plans were supposedly being made, Julia turned up, saying that (in Alf’s words, quoted by Davies) she “wanted John back”. But, in Alf’s recollection, “I said I was now so used to John I was going to take him with me”. He even suggested that Julia come with them and “start again”. After she refused, Alf suggested they “let John decide”.

This is when the notorious incident supposedly occurred. In Alf’s words, reported by Davies:

“I shouted to John. He runs out and jumps on my knee. He clings to me, asking if she’s coming back. That’s obviously what he really wanted. I said no, he had to decide whether to stay with me or go with her. He said me. Julia asked again, but John still said me. Julia went out of the door and was about to go up the street when John ran after her. That was the last I saw of him or heard of him till I was told he’d become a Beatle.”

There are more details in Daddy, Come Home – the 1990 book by Alf’s second wife Pauline, which is “largely based on the text of Freddie Lennon’s unpublished autobiography”. Here, we’re told that the plan was first for John to move to New Zealand with Billy Hall’s parents:

“Mum and Dad are emigrating to New Zealand now that I have enough money to open a business there,” [Billy Hall] told Freddie. “They’re knocked out by your John and think it would be a good idea if they took him with them and we could join them over there as soon as they are settled.”

By this, the book explains that Alf and Billy would “take stewards’ jobs on a ship sailing to New Zealand and leave it on arrival” – a practice known as ‘jumping ship’ that was “very much in vogue at the time”.

And yet in Lewisohn’s Tune In, we are told that the story, as it had become widely told, was “fantasy”. Commenting on the supposed plan that “Billy’s parents would emigrate and take John with them, to be joined later by Alf who’d work a passage there”, Hall told Lewisohn:

“There’s no truth at all in that. I said I would go to New Zealand, and Lennie [Alf] said he might too, and also another mate of ours, and at some point it was mentioned that it would be a great place to raise Johnny [John] – but no plans were ever made. Not only were my parents not planning to go, they didn’t even know Iwas.”

That comment seems to refute Alf’s version decisively. But it’s worth looking closely at what has been disproved here and what hasn’t. Because turns out that there is more to this story than I realised.

Billy Hall’s move to New Zealand

Based on the reported quote from Billy Hall – “no plans were ever made” – I had previously assumed that no one involved in this incident had ever actually emigrated to New Zealand. In fact, Billy Hall did move there. Indeed Bill Hall, as he was later known, became a successful businessman in the country, not only founding a high-profile fashion company, but also becoming a noted figure in game fishing.

An obituary published in 2013 tells us that Bill moved to New Zealand in 1947 – where his early jobs included working in a coal mine and selling millinery. In 1961, Hall co-founded the clothing brand Society Fashions, which was influential in backing new trends and stayed in business until 2020. Following his death, Hall has been hailed as “the man who gave NZ the miniskirt”, who “had a great eye for fashion and could pick a best-seller”.

While he was discreet about his Lennon connections for much of his life, in March 2009 Hall spoke publicly about them, in a three-page interview in New Zealand’s Sunday Star-Times newspaper. As the journalist who met him, Steve Braunias, later recalled, Bill said he was struck by how “well-mannered and well-spoken” the young John Lennon was, looking as though “he’d just come out of a public school”. John “seemed much older” than his young years, said Hall, who recollected that “you could talk with him almost like an adult. He impressed me no end.”

Last year I spoke to Bill Hall’s daughter Josie, who confirmed that her father made several trips to New Zealand with the merchant navy during the war. He took a liking to the country, and decided to relocate there after the conflict ended, with “good parties” being an important motivation. Josie believes her Wigan-born father found it a refreshing change from class-bound Britain. She thinks his impression at the time was: “I've come somewhere, and I'm right round the world, and I'm enjoying this, and things are different, and it looks like fun.”

A passion for the good things in life apparently stayed with Bill. “He liked to laugh. He always drove Jaguars, and [was] always immaculately dressed,” Josie recalled. “And [he] liked to party – always heaps of parties.” Evidently, he also felt strongly about challenging the more dramatic accounts of the events in Blackpool. Even before the emphatic denial reported by Lewisohn, Hall had told Braunias that the version told by Lennon biographer Philip Norman was “bullshit”. So, what did happen?

Bill Hall and Alf Lennon

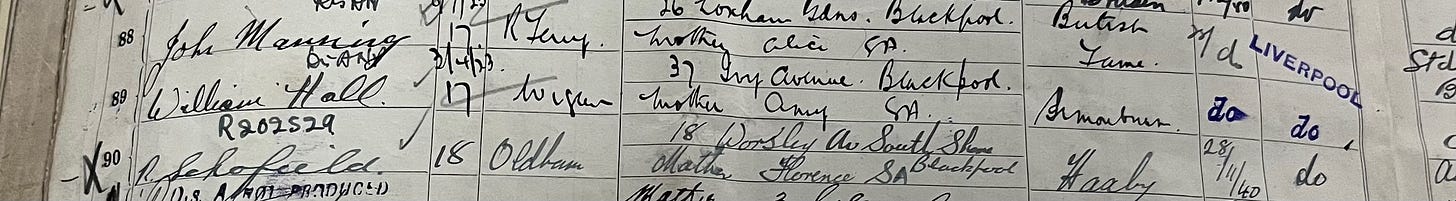

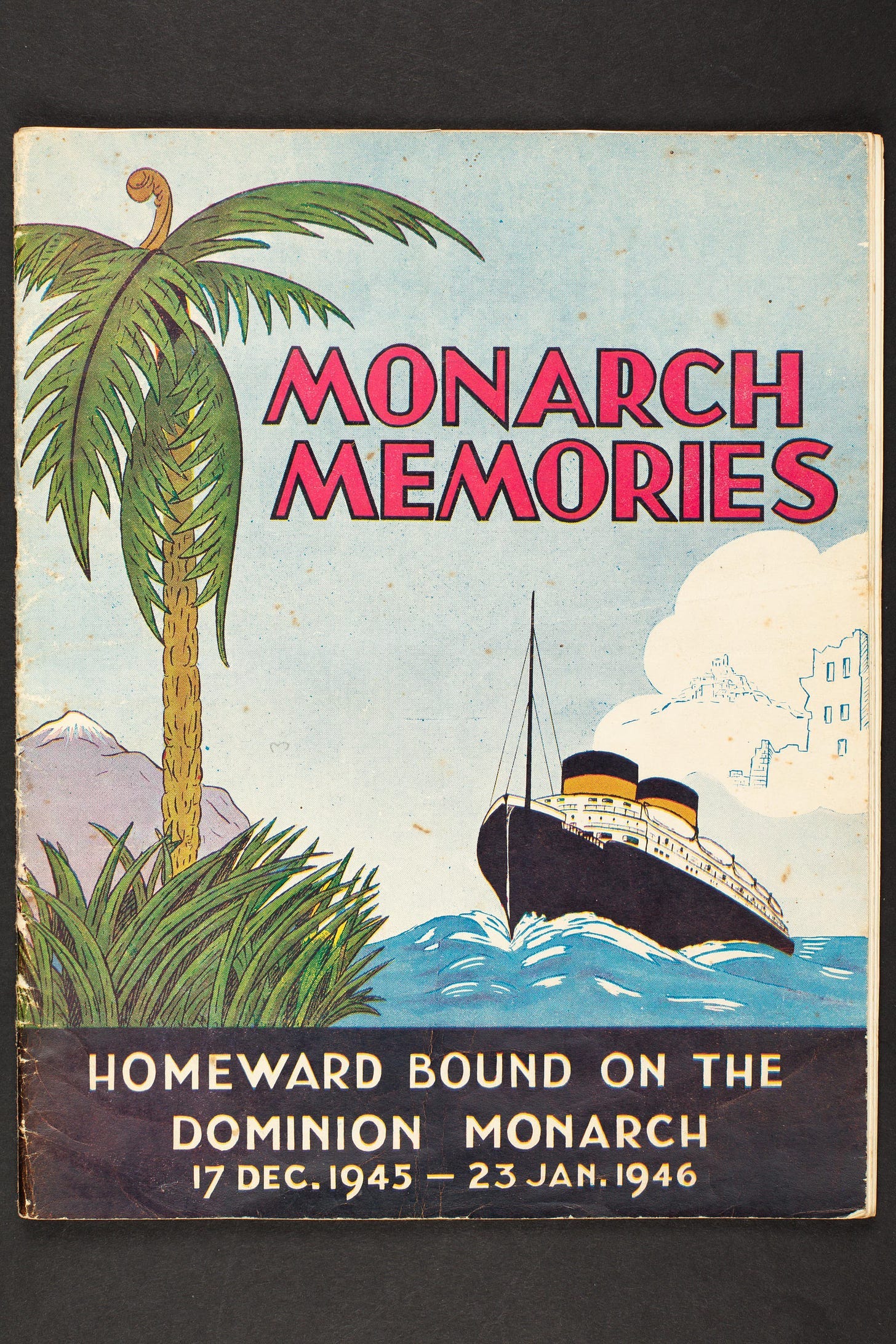

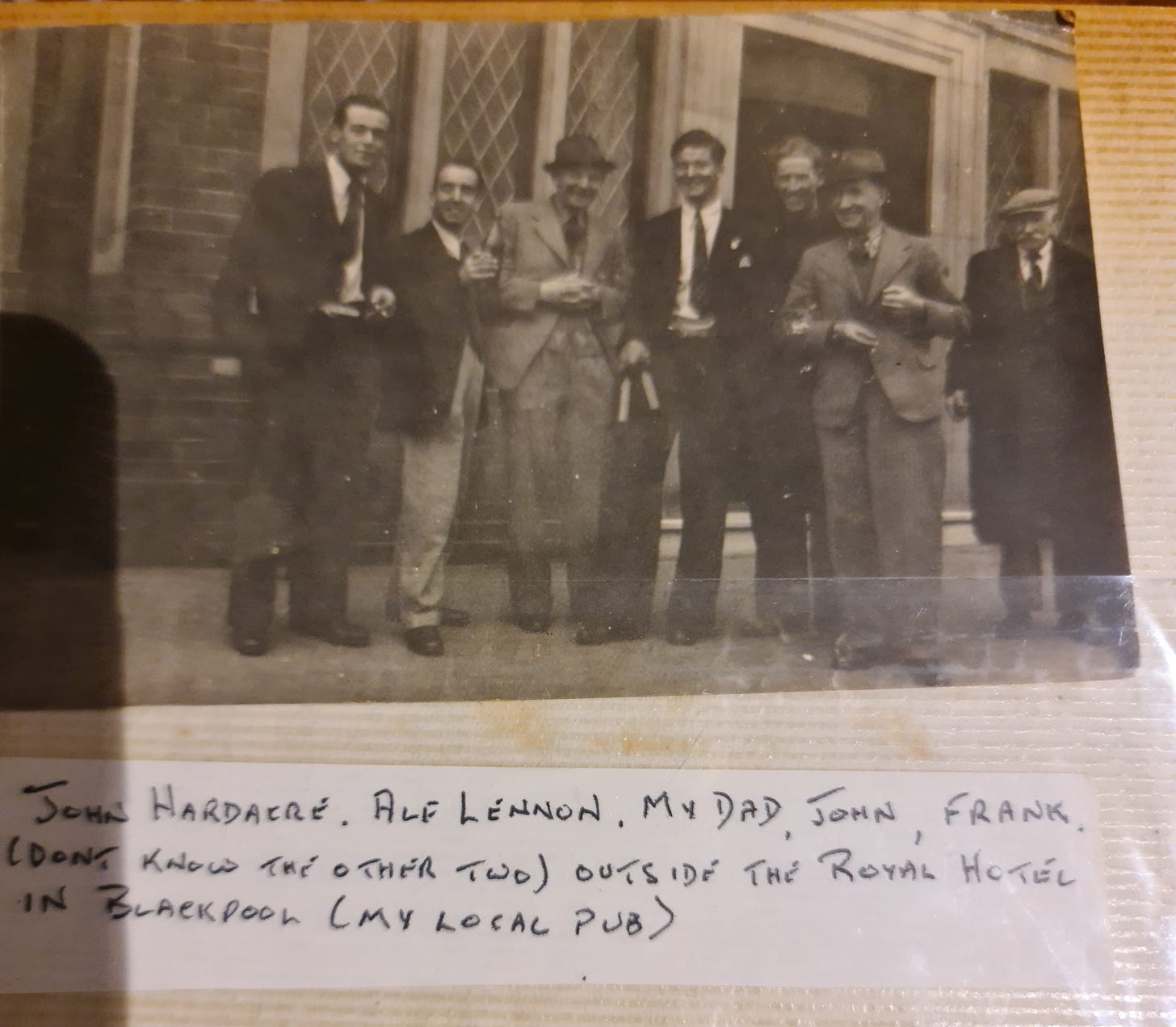

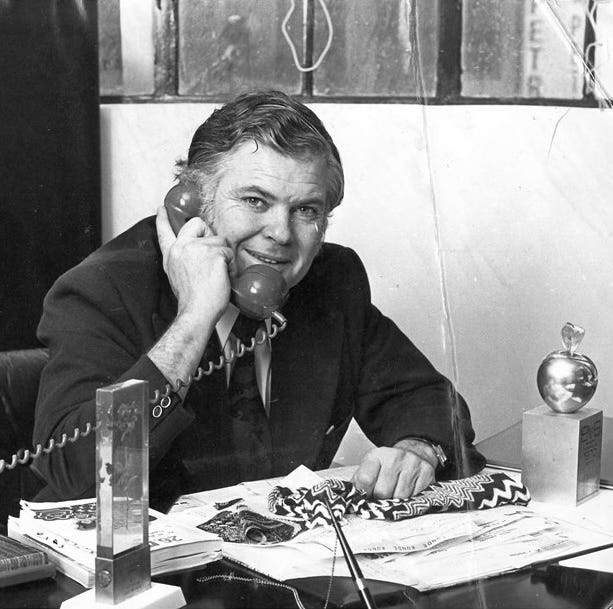

It’s certainly true that Bill Hall and Alf Lennon were friends in the merchant navy during the war. Hall told Braunias that Alf was a “fantastic fellah” who was “fun all the way through. Life and soul. A great entertainer. He was always singing. He sang quite well, actually. A powerful voice…”.4 To Lewisohn, he added that Alf was “a rascal. An absolute character” who was “always part of the fun – and if there wasn’t any, he’d make some”. Bill’s photograph collection included one of him at sea together with Alf, Bill’s brother John, and two other friends, captioned “five good friends” (see above).

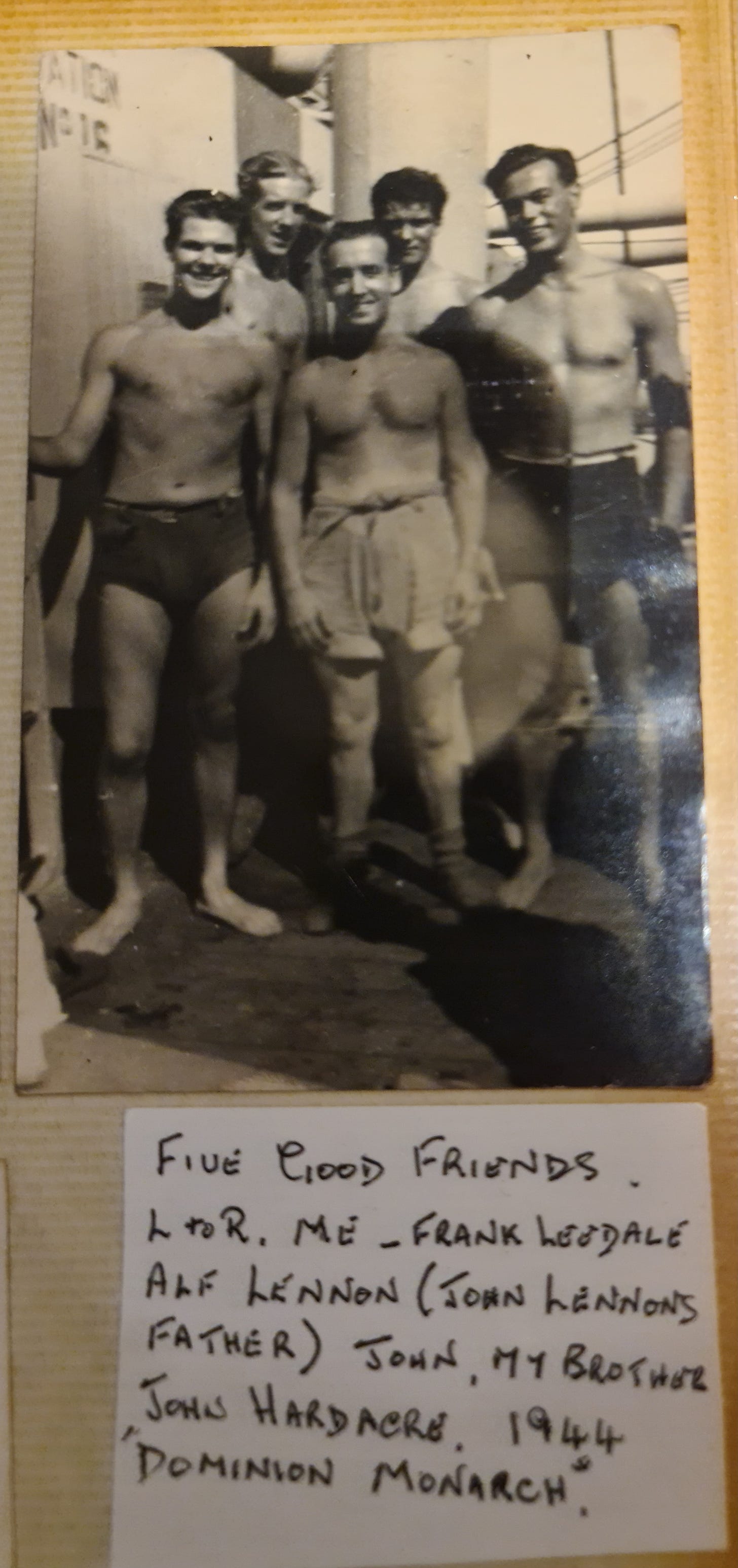

Bill’s note says the photo was taken in 1944 on a ship called the Dominion Monarch – an ocean liner that often plied the route between the UK and New Zealand, via Australia. Originally designed for carrying cargo and first-class passengers, it was (like many similar vessels) requisitioned and repurposed for transporting troops during the war. Before making the return voyage, the ship would harbour for days or weeks in Kiwi ports such as Auckland and Wellington, meaning crew members had time to see the destination – whether on permitted downtime or going absent without leave (Awol). Bill and Alf certainly seem to have taken the opportunity to unwind. Based on his interview with Hall, Lewisohn tells us of a time “in 1944 or ’45” when the two were “making whoopee around the streets of Wellington” and were reprimanded by a policeman after stealing a bicycle.

Josie says Bill had a strong personality and “really took people with him”. So it also seems possible that he and Alf discussed moving to New Zealand while their ship was docked there – and that this idea persisted in their minds until 1946 in Blackpool. Of course, during a war, no plans can be made particularly firmly. “I get the picture that it was pretty much ‘live for the moment and try and grab something’,” says Josie. “I don't think they were too organised.”

How plausible was Alf’s plan?

As we know, Bill Hall did go ahead with his dream of emigrating. And if he was able to do this by working a passage and jumping ship, then presumably it would have been possible for Alf Lennon to do the same. However, taking a five-year-old boy along would have been a completely different matter: the idea that Alf could have done this with John accompanying him is implausible. The account in Daddy, Come Home claims that the plan was for John to move to New Zealand with Bill Hall’s parents, and then for Alf and Bill to join them there later. While this seems on the face of it more believable, it also presents problems. To get to New Zealand, Bill’s parents would have needed an actual passenger ticket. That not only would have cost money – it also wouldn’t have been possible until significantly later than 1946.

The ocean liners that were stripped out to carry troops during the war didn’t immediately revert to passenger service. The Dominion Monarch, for example, didn’t resume passenger voyages from the UK to New Zealand until December 1948, following a 15-month refit. In fact, Bill Hall’s son, Peter, told me that while Bill’s parents did eventually also move to New Zealand (as did his brother John), this wasn’t until several years after Bill himself had emigrated. The existence of these practical difficulties supports Bill’s dismissals of Alf’s supposed plan to move John to New Zealand. In Josie’s view: “The part that is true is that they had discussed coming out here. The part that isn't true is that they didn't actually get together to try and abduct John and take him away.”

Bill and Alf’s accounts don’t match at all

In 2002, Bill Hall published a book, Marlin Fishing, which contains some autobiographical anecdotes. He tells us that he came to New Zealand in 1947, working as a saloon waiter on the Arawa, the “first peace-time passenger ship” to make this trip after the war. After jumping ship in Wellington, Bill then worked in the mines on the country’s west coast for six months, he writes, before later moving to Auckland. Hall also tells us he had visited the country during the war three times. That all sounds believable, and it matches with what Bill’s family and media reports say. However, there’s a real problem aligning it with the account given by Alf Lennon, which tells a very different story.

Daddy, Come Home says that following the Blackpool incident, Alf felt a “gaping emptiness”, and embarked the same month on an 18-month voyage on a ship called the Almanzora. Returning to a “bitterly cold” Christmas, Alf remained downhearted, and at the turn of the year was still hoping his old family life might one day be “restored”. He embarked on two trips on the Andes in 1948, and upon his return, learned that “Mr and Mrs Hall had already left for Auckland”. The book adds that while Bill and his brother John remained in England, “it was understood” that the two Hall sons and Alf “would join [the parents] later, once they had obtained jobs on an ‘Aussie run’”. After hearing that there had been no change in Julia’s situation, we’re told that Alf decided to “leave England for good” – joining Bill and John on the Dominion Monarch to New Zealand. According to Alf, it was not until this point that Billy jumped ship in Wellington, and “paid the penalty of six weeks’ breaking sandstone”.

The book says Bill intended to try to arrange for his brother and Alf not to have to do this, which is why they planned to wait one more trip before jumping ship. But on the next visit to New Zealand – in October 1949 – we’re told that Alf had second thoughts, and decided to try again to convince Julia to allow John to emigrate there with him. On his return to England, however, Alf ended up in London’s Wormwood Scrubs prison after a drunken pub crawl that culminated with him breaking a shop window and stealing a mannequin. As a result, it became impossible for him to be employed on a ship again. With his family and career gone, Alf by now felt there was “nothing left worth living for”. He briefly became an itinerant “gentleman of the road” before finding work as a hotel kitchen porter.

The unreliable Alf?

Taken on its own, much of the account in Daddy, Come Home sounds plausible (if perhaps somewhat embellished), and several of John Lennon’s biographers have clearly made use of it. But it certainly doesn’t match Bill Hall’s version – describing a voyage to New Zealand with Bill at a time when, according to Hall himself, he’d already living there for about a year. Alf’s quasi-autobiography wasn’t published until 1990, leaving plenty of time for aspects to become embellished. The book, however, does discuss the relevant events in some detail – claiming Alf persisted with the hope of moving with John to New Zealand as late as 1949. If his story is all an invention, it’s quite an elaborate one. And how much of its other information could we then trust?

Alf’s accounts of his travels at sea are fascinating in other ways – not least in what they suggest about his character. In claims I’ll write about in more detail in my next post, he tells us how after deserting his ship in New York, he was detained by authorities on two other occasions during an extraordinary 16-month series of mishaps – including a stay in a military prison in Algeria. In fact it was shortly after this incarceration, according to Alf, that while preparing to return to the UK he met “a friendly young steward by the name of Billy Hall … and so a long friendship began”.

The story prompts some scepticism – not least because each time he found himself behind lock and key, Alf portrays himself as an unfortunate victim rather than taking responsibility. Supporting his credibility, though, he names specific ships he travelled on, sometimes giving very specific dates – and some of these details appear to closely match those in online shipping records. And while Bill Hall’s story seems to stack up, we should remember that by the time he spoke to Braunias and Lewisohn, he was in his mid-eighties. He slipped up with the timing of the Blackpool events, telling Braunias they took place in 1945 rather than 1946. Given this, how sure can we be about the 1947 date that he recalls for his emigration?

With these complexities, a lot still remains uncertain about Alf’s wartime escapades, his friendship with Bill Hall, and the events surrounding the Blackpool conversation. Whatever happened, it seems there was little realistic possibility of the five-year-old John Lennon moving to New Zealand. On the other hand, it’s very plausible that the idea of John’s father – and possibly John himself – emigrating there was discussed. So as I’ve suggested before, the rupture with Alfred that took place then could conceivably have been associated in John’s young mind with the idea of moving to an island.

That possible connection was my initial reason for my interest in the Blackpool story. But having learned more about these events, I now wanted to resolve their puzzles. Why do Bill Hall and Alf Lennon’s accounts vary so dramatically? And if Alf was aiming to deceive, why would he provide so many bizarre details – some of which seem to be accurate?

Lewisohn notes that “Alf did spin yarns” and admits that it can be “difficult… to establish the veracity of [his] stories”5. However, after venturing deep into shipping archives, I’ve found some fascinating documentary evidence that not only removes a lot of the doubt – but also reveals significant new details. There are indeed a lot of tall stories in what Alf Lennon says – though in some ways, the truth is even stranger. I’ll write about what I discovered in my next post: subscribe below to make sure you don’t miss it.

Update - read my research on Alfred Lennon’s wartime experiences:

Tim Riley, New York Times, 6 December 2013

John Lennon: The Life (2008)

The Beatles (1968)

Sunday Star-Times, 8 March 2009

Tune In, extended special edition (2013)

Even as a kid, reading Alf's accounts of things always made me skeptical. Many of the people in young John's life seemed to put their own interests before his.