The historian and the mystery of Billy Hall’s birthday

Mark Lewisohn’s error over when the key witness to the ‘Blackpool incident’ was born highlights the challenges of researching Beatles history in the digital age

While I was writing last month about the evolution of the ‘Blackpool tug-of-love’ myth, a new puzzle came to light – which prompts interesting questions about how the way we research and talk about the Beatles is changing in the digital age.

The issue raised the possibility that when discussing these events with the eminent Beatles historian Mark Lewisohn, Billy Hall got his own date of birth wrong. If this happened, it would of course cast serious doubt on the reliability of Hall – whose testimony was central to overturning the traditional narrative. But the only other explanation would be if the inaccuracy came from Lewisohn himself.

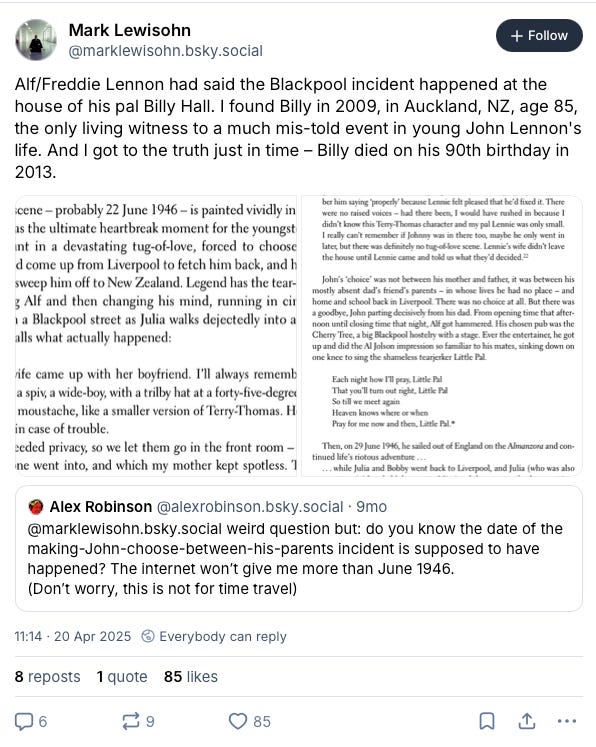

The conundrum related to a post Mark Lewisohn made on the Bluesky social network in April 2025. In response to a query from another user, he wrote (bold added for emphasis):

“Alf/Freddie Lennon had said the Blackpool incident happened at the house of his pal Billy Hall. I found Billy in 2009, in Auckland, NZ, age 85, the only living witness to a much mis-told event in young John Lennon’s life. And I got to the truth just in time – Billy died on his 90th birthday in 2013.”

The birth date mystery

From my research into these events, I was aware that Billy (later known as Bill) Hall had spoken to a New Zealand journalist – Steve Braunias of the Sunday Star-Times newspaper – in 2009, shortly before he spoke to Lewisohn. According to Braunias, Lewisohn had contacted him after the interview was published – and as a result, Braunias in turn put the historian in touch with Hall.

In December, I emailed Mark Lewisohn to check this timeline and offer him the chance to add anything further. I quickly received a detailed response setting out Lewisohn’s history of contact with Bill Hall and his family. He confirmed Braunias’ sequence of events – explaining that he approached the Sunday Star-Times in 2009 after being alerted to the reporter’s interview with Hall. Braunias then “kindly paved the way” for Lewisohn to speak to Bill, which happened in April 2009.

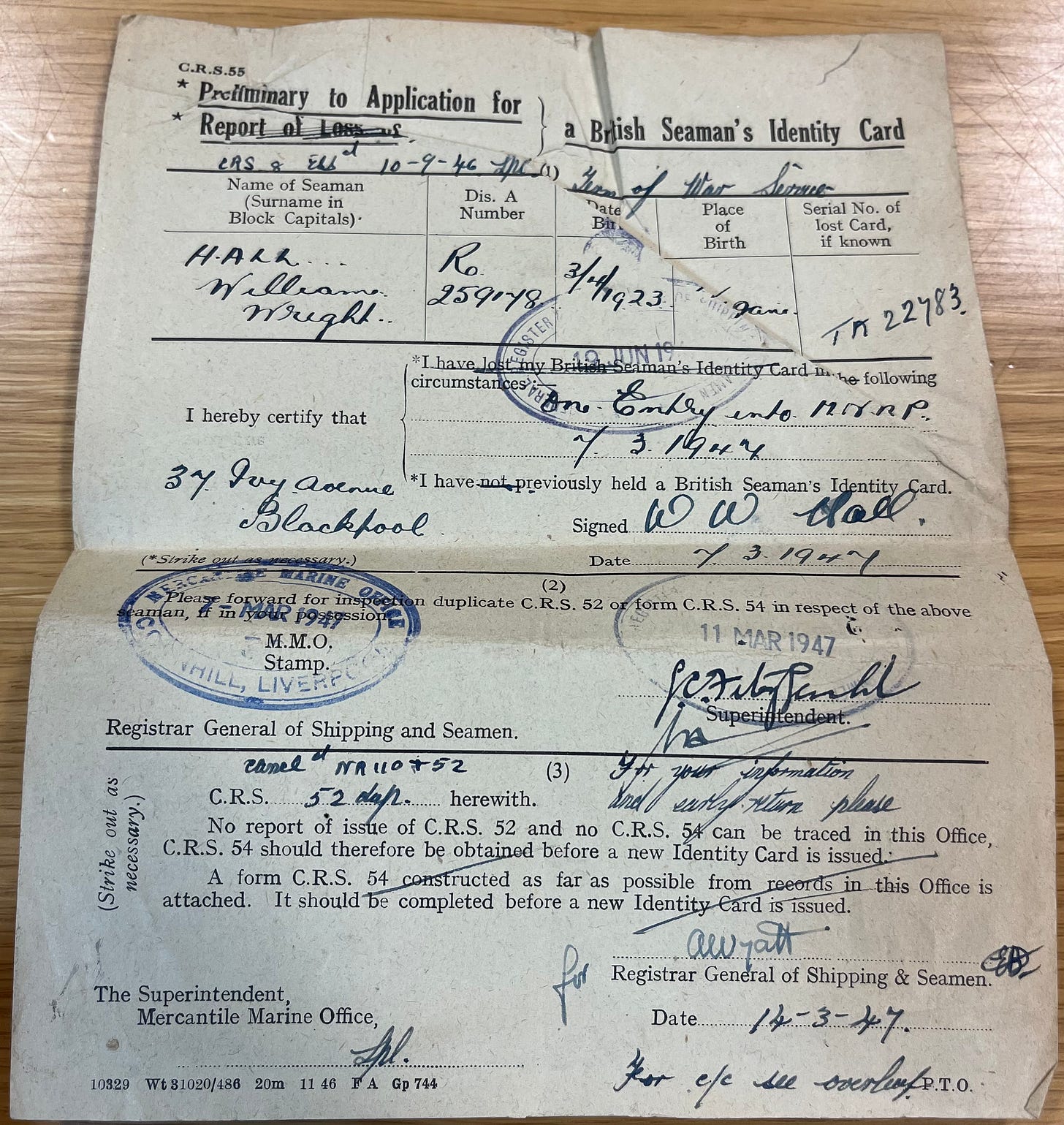

The email also included an explanation for a detail I hadn’t asked about – Mark Lewisohn’s claim that Bill died on his 90th birthday. Lewisohn wrote that Hall was “born 3/9/1923 in England; so, time zone difference allowing, he died 90 years to the day that he was born”.

As confirmed in a Sunday Star-Times obituary, Hall did indeed die on 4 September 2013. But Bill’s birthday had also come up in my own research, and the date given by Lewisohn for this seemed to contradict what I thought was the case. I asked Lewisohn if he had a source for the birth date being in September, noting that I thought it was in April. He replied: “He told me his date of birth and I’d no reason to doubt it, and still don’t.”

Given this seemingly emphatic response – and since the timing of Bill’s birthday was not relevant to the post I was writing – I put the issue to one side. But later, I checked my records in detail. It turned out that in National Archives files I’d seen, there were five separate official documents all stating Bill Hall’s date of birth as 3 April, 1923. Bill’s daughter Josie had told me the same specific date when I spoke to her in 2024.

There seemed little doubt that Bill was born in April, not September. Confused, I contacted Mark Lewisohn again, sending him a copy of one of the documents. Then the mystery was solved: Lewisohn acknowledged that he’d made an error in his email to me – and that Bill had in fact told him his birthday was in April, not September.

The Bluesky post which stated that “Billy died on his 90th birthday” hadn’t so far been specifically discussed in our email exchange. I emailed Lewisohn this week to confirm whether the post was inaccurate. I explained that I planned to write about the issue “as an example of the complexity of Beatles research in the digital age” and offered him the chance to comment. He responded:

“I continually have the sense that you’re trying to call me out for something. I do hope I’m wrong about that, just as I was wrong when reporting Hall’s birthdate in a social media post and repeating it in an email without rechecking the source. That’s what comes of momentarily and not properly diverting my focus from writing Volume 2 [of his Beatles biography]. I expect you’ll also have made a mistake at some point in your life.”

At the time this Substack post was published (14 January 2026), Mark Lewisohn’s Bluesky post remained online.

Beatles history in the digital age

As Lewisohn’s response suggested, historians and researchers will always make mistakes. But the now-solved mystery of Billy Hall’s birthday highlights how easy it is for historical narratives to become distorted when they are not closely based on documents. And as errors are disseminated through different channels, they may begin to become entrenched and more difficult to challenge. As Lewisohn’s comment alluded to, such risks increase on social media, where posts are often composed quickly and may receive less rigorous verification than claims in other formats.

Mark Lewisohn doesn’t need reminding of the central importance of documents to historical research – it’s a point he’s repeatedly made himself. And in the wider scheme of things, the date of Billy Hall’s birth is a minor detail. Even so, the error here underlines how misunderstandings can enter the discourse on even the most apparently straightforward matters.

As Lewisohn pointed out to me, this mistake was thankfully not included in his Beatles biography, Tune In. But this raises a further important point. Increasingly, Beatles research is being carried out and discussed not just in the printed media, but also through faster-moving, more informal formats such as blogs and podcasts. And most researchers, including Lewisohn, are using digital platforms to engage with their audiences.

The conversational nature of these spaces is a strength. And instinctively, many would give more leeway to remarks made on a podcast or a social network than those in a book or scholarly journal. But when these comments – whether made by Lewisohn or anyone else – have a direct bearing on our understanding of the Beatles, does that still make sense?

As the influence of online platforms grows, this is a question that anyone interested in Beatles history will have to think carefully about. Some podcasts and blogs include extensive citations and explicitly consider evidential questions – exhibiting stronger scholarly rigour than many printed books. This surely points the way forward: not lowering the bar for some media, but maintaining high standards across the board. Achieving this, while maintaining the accessibility and liveliness of digital media, will support an increasingly better understanding of the Beatles’ story.

Read more:

Lewisohn has come under lots of fire (unwarranted in my opinion) over what people say is his version of facts, which certainly would be distracting. But as I'm still reading newer books than his that spew previously debunked falsehoods, I'm glad he's taking his time with volumes 2 and 3.

That said, I also hold "Follow The Sun" as a highly reliable source, as I'm sure he also will once he's finalized his coverage of the Greece angle. Keep up the great work!

Thanks for your kind words - appreciate it!